Newsletters

- Home

- Publications

- Newsletter Archive

- Newsletter

September/October 2016

Inside This Issue:

- Victim Services and Criminal Justice Responses to Domestic Violence in Rural Pennsylvania

- Board Thanks Sen. Wozniak for Service

- Chairman's Message

- Rural Snapshot: Poverty in Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Voter Participation Rates

- Did You Know . . .

- Just the Facts: On the Right Track

Victim Services and Criminal Justice Responses to Domestic Violence in Rural Pennsylvania

Awareness of domestic violence (DV) has increased over the past three decades, and so have the victim services and criminal justice responses to such incidents, overall. In rural areas, however, victim services face unique challenges in helping DV victims, and criminal justice responses to DV cases remain uneven, according to the results of two research projects sponsored by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania.

Both research projects were conducted in 2015. The first study examined DV shelter services in rural Pennsylvania counties and was conducted by Dr. Gayatri Devi, Dr. Tara Mitchell, Dr. Nicole Burkholder-Mosco, Dr. Lisette Schillig, Dr. Holle Canatella, Dr. Katie Ely, and Sara Guthrie of Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania. The second study investigated DV cases brought before Magisterial Courts in rural Pennsylvania and the manner in which these courts commonly handle DV cases. The research was conducted by Dr. Gabriela Wasileski and Dr. Erika Davis-Frenzel of Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Victim Services

In their examination of DV victim services in rural Pennsylvania, the researchers from Lock Haven University found that shelters in rural counties have critical resource gaps, such as the availability of public transportation and transitional housing. The researchers also found that shelters in rural counties rely more heavily on community partners, such as faith-based groups and businesses, for resources than shelters in urban counties.

The study, Analysis of Domestic Violence Services in Rural Pennsylvania, focused on the 60 domestic violence service centers/shelters funded through the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence (PCADV), a publicly funded coalition of domestic violence centers in the state. The researchers used secondary data from PCADV and the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency, and conducted a survey and focus groups with shelter personnel and clients. The researchers used the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s definition of rural and urban counties.

The research found that, in general, adult females were most likely to use shelter services, followed by girls. In urban shelters, adult females were again most likely to use shelter services. However, all other age groups, including girls, boys, adult males, and senior citizens, used services without showing significant differences based on age. The research also found that shelters in rural counties noticed a generational and intergenerational indifference toward interpersonal violence.

Shelters in rural counties provided more referrals to child custody assistance and more social services support than shelters in urban counties.

In terms of funding, rural shelters received less funding, overall, than urban shelters. However, rural shelters received more funding per capita than urban shelters. Rural shelters allocated more funding toward community outreach, transportation, and full-time employment, while urban shelters allocated more funding toward facilities and part-time employment.

Overall, the research found that rural shelters face unique challenges in helping survivors of domestic violence. It offers several policy considerations regarding federal and state government programs, law enforcement intervention, transportation and legal services to address the challenges.

Magisterial Courts

Using interviews and secondary data, the researchers from Indiana University of Pennsylvania examined DV cases brought before Magisterial Courts in rural Pennsylvania and the manner in which these courts commonly handle DV cases.

For the study, Domestic Violence Cases in Rural Pennsylvania Magisterial Courts: Practices, Effectiveness and Consequences, the researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with 27 magisterial judges in 21 rural counties across Pennsylvania.

They defined the perpetrator of domestic violence as a person who was currently or recently in an intimate relationship with the victim, who might be a spouse or boyfriend/girlfriend. The study eliminated the category of domestic violence against children, parents, siblings or other family members related by blood or marriage.

Overall, the research found efforts to criminalize DV have improved policing of DV, increased victims’ reporting of abuse to officials, increased the number of DV arrests, often of both parties, and increased the number of issued Protection from Abuse orders.

The largest barrier faced by district judges in determining consequences for offenders was the unwillingness of DV victims to testify against the abuser. Even when victims testify, cases are often reduced to summary offenses, which are less than misdemeanors. As a result, offenders do not have criminal records that could possibly influence future evidence-based assessments of the risks to victims. Additional research needs to explore the possibility of changes in processing, such as evidence-based prosecution, which would not rely on victim testimony.

Additional barriers faced by the district judges included a lack of available treatment programs for DV offenders and an absence of the Magisterial Courts’ legal jurisdiction to mandate treatment programs for those DV offenders who are willing to be enrolled in court-mandated treatment programs.

The findings suggest the need for a graded range of disposition available to magisterial judges, such as court-mandated domestic violence treatment or possibly substance abuse counseling if the offender was consuming drugs or alcohol at the time of the offense.

Reports Available

Copies of the research reports, Analysis of Domestic Violence Services in Rural Pennsylvania and Domestic Violence Cases in Rural Pennsylvania Magisterial Courts: Practices, Effectiveness and Consequences are available on the Center’s website at www.rural.palegislature.us/publications_reports.html.

Board Thanks Sen. Wozniak for Service

At its August meeting, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania's Board of Directors recognized Board Vice Chairman Sen. John Wozniak for his 14 years of service to the Center for Rural Pennsylvania and the board. During his tenure, Sen. Wozniak also served as treasurer. Sen. Wozniak is retiring at the end of the year. Pictured left to right: Steve Brame, Rep. Garth Everett, Sen. Wozniak, Sen. Gene Yaw, Dr. Karen Whitney, and Dr. Stephan Goetz.

Chairman's Message

According to a July 2016 report from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Philadelphia Field Division’s (PFD) Intelligence Program, more than 3,300 people died from an overdose in Pennsylvania in 2015. That same report cited a 23.4 percent increase in the total number of overdose deaths in Pennsylvania from 2014 to 2015. Sadly, information being collected this year will most likely point to an increase in overdose deaths for 2016. The continuing increase in drug-related overdose deaths certainly confirms a clear and present crisis for our state’s law enforcement, public health agencies and educators to combat drug availability, provide drug treatment and promote drug education.

Over the past 3 years, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s Board of Directors has heard first-hand testimony about the heroin/opioid epidemic and what the community, law enforcement, treatment and health care professionals, educators and state and local governments are doing to address this crisis. The Center’s work has laid the foundation for greater awareness by the General Assembly in coordinating a statewide response. A number of bills already have been introduced in the Senate and House of Representatives to address various aspects of the epidemic. And, the Center’s board and staff continue to work with the Department of Drug and Alcohol Services, the Department of Health and the Physician General’s Office to help spread the word about the importance of the life-saving drug naloxone and on the implementation of the prescription drug monitoring program.

On September 20, the Center’s Board will sponsor its 11th public hearing on the heroin/opioid epidemic at the Kovalchick Convention and Athletic Complex at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. With this hearing, which is being hosted by Sen. Don White, the Center hopes to continue raising awareness of the issue and gather more information for the legislature and the state as a whole. The testimony that the Center has gathered to date is on my website, and more information about the hearings and the summary reports from the hearings are available on the Center’s website.

On behalf of the Center’s Board, I want to take this opportunity to thank Sen. John Wozniak for his 14 years of dedicated service and commitment to the Center for Rural Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania’s rural communities overall. Sen. Wozniak is retiring from the Senate at the end of the year, but I know that his work to support the growth and vitality of rural Pennsylvania will remain strong.

Senator Gene Yaw

Rural Snapshot: Poverty in Pennsylvania

Background: This installment of Rural Snapshot looks at poverty in Pennsylvania. For the analysis, the Center used the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service's 2016 federal poverty level (FPL) income numbers, which are based on household income and household size. In 2016, the poverty level for a family/household of three is $20,160.

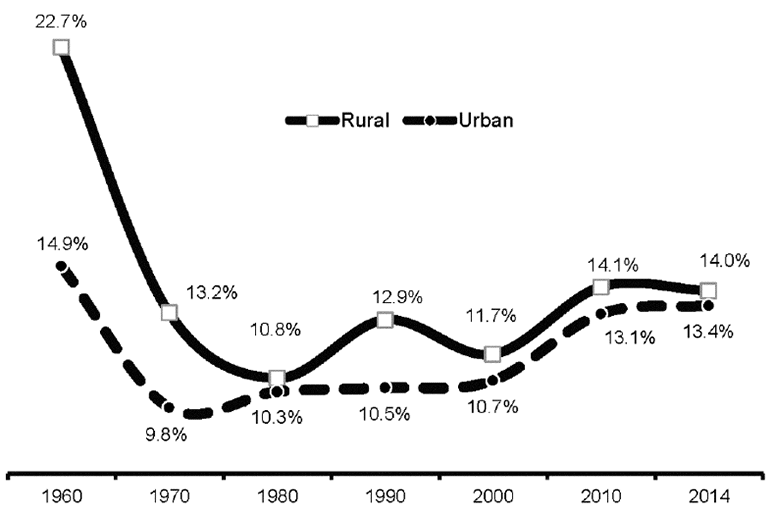

Poverty Rate in Rural and Urban Pennsylvania, 1960 to 2014

Data sources: 1960 to 2000 Censuses and 2010 and 2014 Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, U.S. Census Bureau.

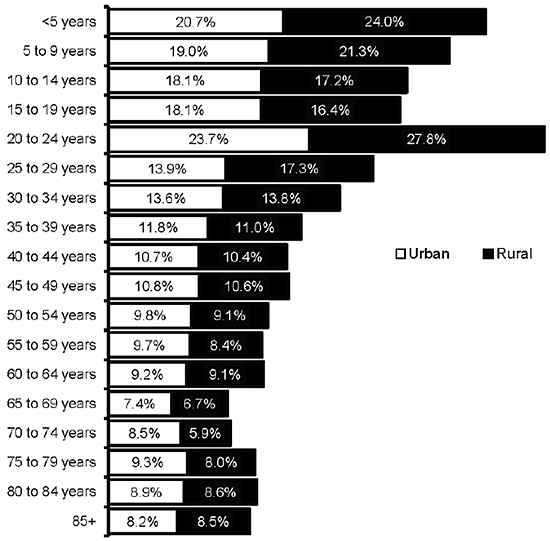

Rural and Urban Poverty Rate by Age Cohorts, 2014

Note: Data exclude persons living in group quarters such as college dorms, nursing homes, prisons. Data source: 2014 American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS-PUMS) U.S. Census Bureau.

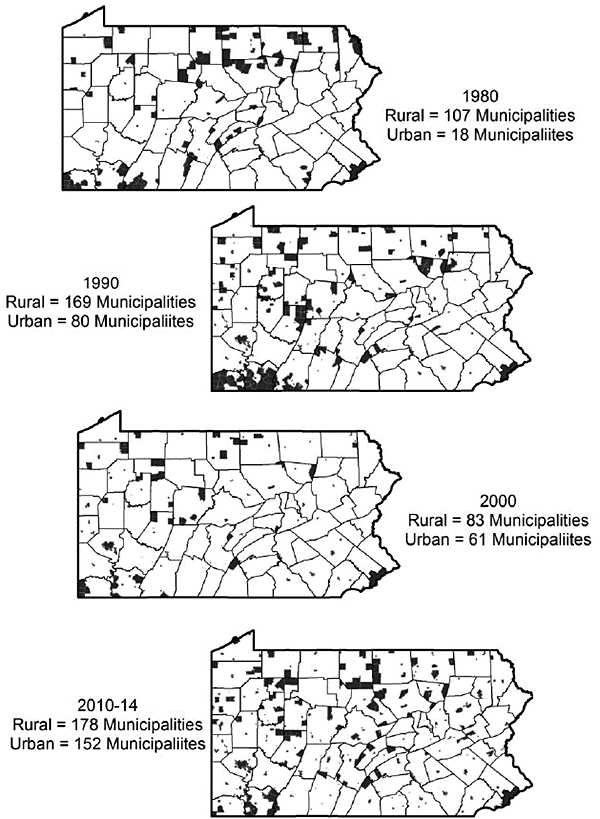

Municipalities with Poverty Rates of 20% or Higher, 1980 to 2010-14

Data sources: 1980 Census, 1990 Census, and 2000 Census and 2010-14 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.

- The poverty rate for rural adults (18+) without a high school diploma was 23 percent. For those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, it was 5 percent.

- The rural poverty rate for unemployed adults (18+) was 32 percent.

- 46 percent of rural adults in poverty were never married.

- 22 percent of rural adults in poverty had one or more disability.

- 18 percent of rural residents in poverty did not have health insurance.

Note: Data exclude persons living in group quarters such as college dorms, nursing homes, prisons. Data source: 2014 American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample.

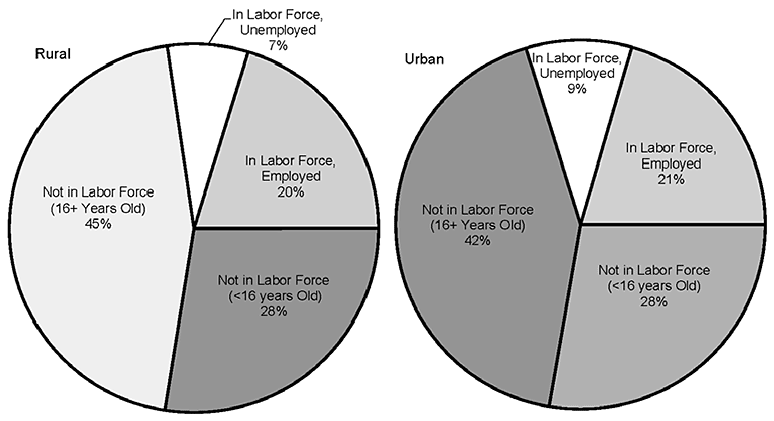

Poverty by Labor Force Status, 2014

Note: Data exclude people living in group quarters such as college dorms, nursing homes, prisons. Data source: 2014 American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS-PUMS) U.S. Census Bureau.

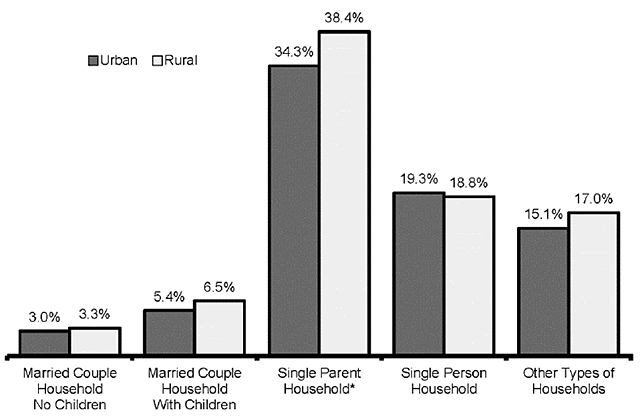

Rural and Urban Poverty Rate By Household Type, 2014

*Single parent household includes male or female headed household with no spouse present and with children (<18 years old). Data source: 2014 American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS-PUMS) U.S. Census Bureau.

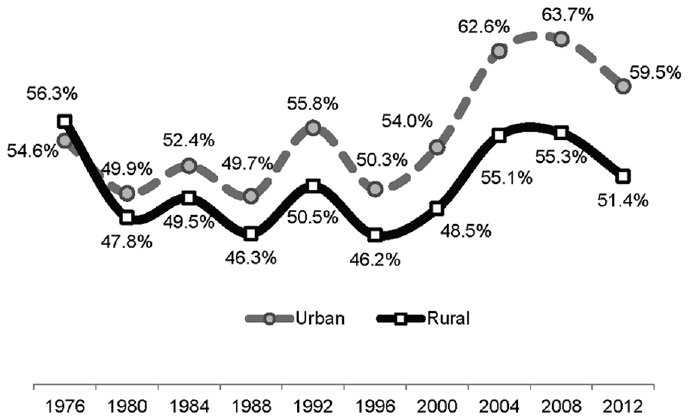

Pennsylvania Voter Participation Rates

Over the last 10 presidential election cycles (1976 to 2012), rural voters had lower participation rates than urban voters, according to data from the Pennsylvania Department of State’s Bureau of Commissions, Elections and Legislation. The average participation rate among rural voters was 51 percent and the average participation rate among urban voters was 55 percent.

The voter participation rate was determined by dividing the number of votes cast for president by the number of persons who were 18 years old and older.

Between 1976 and 2012, 1.27 million rural residents, on average, voted during a presidential election. During this period, however, there were some peaks and valleys. For example, the two highest peaks were in 2004 (G.W. Bush vs. Kerry) and in 2008 (Obama vs. McCain). During these two presidential elections, more than 1.46 million rural voters, or 55 percent, cast ballots.

The two valleys were in 1980 (Reagan vs. Carter) and 1988 (Bush vs. Dukakis), when 1.14 million rural voters, or 47 percent, cast ballots. These peak-and-valley patterns were similar among urban voters.

Data from a 2012 PEW Research Center survey indicated the average age of rural voters in the U.S. is 52. Fifty percent of these voters are female, white (88 percent) and have some level of college education (55 percent). When asked where they got their information on the presidential campaign, 74 percent said television, 9 percent said newspapers, 8 percent said radio, and 8 percent said the Internet.

Fifty-three percent of rural voters said campaign commercials were not helpful in their decision making.

Rural and Urban Pennsylvania Voter Participation Rates in Presidential Elections, 1976-2012

Data Source: Pennsylvania Department of State's Elections Bureau.

Did You Know . . .

In 2014, there were about 254,000 students enrolled in colleges or universities in rural Pennsylvania.

Did you know:

- 54 percent were female and 46 percent were male.

- 86 percent were undergraduates and 14 percent were in graduate school.

- 73 percent attended a public college or university and 27 percent were enrolled in a private college or university.

- 66 percent were born in Pennsylvania, 27 percent were born in another state, and 7 percent were born outside of the U.S.

- 88 percent were white, and 12 percent non-white.

- 25.1 was the average age of a student and 10 percent of students were 40 years old and older.

- 16 percent were married.

- 54 percent were employed: 60 percent worked part-time (<35 hours per week) and 40 percent worked full-time (35+ hours per week).

- 67 percent lived in a dorm or some other type of group quarter.

Data source: 2014 American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample, U.S. Census Bureau.

Just the Facts: On the Right Track

There are nearly 3,000 miles of active railroads in rural Pennsylvania, according to 2016 data from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT). That’s 55 percent of the more than 5,400 miles of rail lines in Pennsylvania.

The majority of rural railroad miles (88 percent) are used to transport freight. Passenger rail makes up 11 percent, and tourist or excursion rail comprises 1 percent of the total mileage.

In urban Pennsylvania, there are approximately 2,450 miles of active railroads. The majority of these railroads (77 percent) also is used to transport freight. Passenger rail makes up 21 percent of the total mileage, and tourist or excursion rail comprises 1 percent of the total mileage.

According to data from the Association of American Railroads, there are 138,524 rail miles in the U.S.

Texas has the most with more than 10,400 miles, followed by Illinois, California, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, each with more than 5,000 miles.

In rural Pennsylvania, there are 3,070 railroad road crossings, or an average of one crossing every railroad mile. Most of the rural road/rail crossings (76 percent) are at grade, meaning there are no underpasses or overpasses across the railroad.

In urban Pennsylvania, there are 4,136 railroad road crossings, or an average of one crossing every 0.6 railroad miles. Fifty-two percent of urban crossings are at grade.

According to PennDOT’s records, from 2010 to 2015, there were 179 vehicle crashes involving trains. Sixty-five of these crashes occurred in rural areas and resulted in nine fatalities. In urban areas, there were 114 vehicle/train crashes that resulted in seven fatalities.

In rural Pennsylvania, 1.3 million residents, or 38 percent of the rural population, live within one mile of an active railroad. In urban Pennsylvania, there are nearly 5.2 million residents, or 56 percent of the urban population, living within one mile of a railroad.