Newsletters

- Home

- Publications

- Newsletter Archive

- Newsletter

May/June 2013

Inside This Issue:

- Fewer Rural Municipalities Experiencing Symptoms of Financial Distress

- Board Awards Research Grant for State Population Projections

- Chairman's Message

- Center Board Elects Officers for 2013-2014

- Rural Snapshot: Young Families

- A Dollar a Dozen? Dollar-Type Retail Stores in Pennsylvania

- Did You Know . . .

- Just the Facts: Rural Tourism

Research Analyzes Financial Condition Data

Fewer Rural Municipalities Experiencing Symptoms of Financial Distress

Fewer rural Pennsylvania municipalities are experiencing the symptoms of financial distress than urban Pennsylvania municipalities, according to 2012 research conducted by Dr. Patricia Patrick of Shippensburg University and Dr. John Trussel of the University of West Florida.

The research, sponsored by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania, analyzed 2007 to 2010 data from the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development’s (DCED) Survey of Financial Condition (SOFC) and found that about 9 percent of rural and 18 percent of urban municipalities were experiencing symptoms of financial distress.

The research also indicated that municipalities experiencing the most symptoms of distress were clustered in the northeast and southwest regions of the state.

Research background

The research analyzed 2007 to 2010 SOFC data to identify municipalities experiencing the symptoms of financial distress. The researchers used socio-demographic, economic, and financial indicators to identify statistical associations with the symptoms of financial distress.

The researchers collected the data on all 2,562 cities, boroughs and townships in Pennsylvania and defined a symptom of financial distress as any “yes” answer on the SOFC form, if the question matched the criteria of financial distress established by the Municipalities Financial Recovery Act of 1987 (53 P.S. §§ 11701.101 to 11701.501 and all amendments), also known as Act 47. The researchers controlled for a municipality’s status as rural or urban and its type as a city, borough, township of the first class or township of the second class.

Results of analysis on financial distress

Overall, the research identified 321, or 13 percent, of Pennsylvania municipalities experiencing the symptoms of financial distress.

Forty-eight percent of cities, about 13 percent of boroughs, 11 percent of townships of the first class, and 11 percent of townships of the second class were experiencing the symptoms of financial distress.

Municipalities answered “yes” 155 times to the SOFC questions in 2007 compared to 286 times in 2010, indicating that the frequency of distress had increased. These symptoms impacted approximately 2.1 million people, 268,840 of whom lived in rural municipalities.

The most common reason for a municipality answering yes to a SOFC question, regardless of the type of municipality, was an excess of expenditures over revenues for 3 or more years. Accumulated deficits of 5 percent or more for 2 consecutive years were also very common.

Rural municipalities were responsible for most of the missed payrolls, failed attempts to negotiate large claims, and bankruptcy filings. Urban municipalities were responsible for nearly all of the unfunded pension obligations and bond defaults.

The municipalities experiencing the most symptoms of distress were clustered in the northeast and southwest regions of the state. The researchers conclude that this distress was likely caused by the migration of the coal and steel industries from these regions several decades ago.

The researchers note that while the commonwealth’s early warning system encourages collaboration, it will be interesting to see whether the efforts of individual municipalities can mitigate the chronic symptoms of financial distress found in these regions, since the remedies for long-term, structural distress usually require significant, new, economic development efforts.

According to the research, financial distress at the municipal level is an inter-governmental problem. It can make state government unstable by threatening its bond-ratings, and putting pressure on it to deliver public services if the distressed municipalities become unable to do so. Municipal financial distress can also affect the willingness of new businesses to move into the area.

The research concludes that state government can play an important role in preventing, detecting, and mitigating the symptoms of financial distress in municipalities, but only if it is aware of the symptoms.

Report available

For a copy of the research report, An Analysis of Survey of Financial Condition Data, call or email the Center at (717) 787-9555 or info@rural.palegislature.us or visit www.rural.palegislature.us.

Board Awards Research Grant for State Population Projections

At its March 11 meeting, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s Board of Directors awarded a grant to Pennsylvania State University-Harrisburg to develop population projections for Pennsylvania. The project director, Michael Behney, and the research team will develop population projections at 5-year intervals for Pennsylvania’s 67 counties for the next 30 years. The Pennsylvania county-level population projections to 2040 will include gender and 5-year-interval age cohorts. The research began in April and will be completed at the end of December.

Chairman's Message

Winter’s grip is finally over and the clear signs of spring are everywhere. One familiar sign of spring is the preparation of fields for planting. Pennsylvania’s agriculture industry is getting ready for another growing season. One important segment of agriculture here in Pennsylvania is the wine industry. Recently, the Center released an assessment report on the wine industry, noting that 81 percent of Pennsylvania wine is being sold directly from wineries or winery outlets. According to the Pennsylvania Winery Association, we have approximately 150 wineries that produce and sell wine throughout the state’s seven wine regions. Pennsylvania is also home to 11 wine trails that contribute $2 billion to the state’s economy.

Spring is also the time when the Center releases its annual Request for Proposals and accepts Letters of Intent for the next research grant award cycle. At its March meeting, the board approved targeted topics that it considers most timely and relevant to our rural communities including an analysis of: the fiscal status of rural volunteer fire companies, municipally owned rural roadways, the economic impacts of state and federal Heritage Areas, Pennsylvania’s health workforce, special education funding in rural and urban school districts, unearned income, self-employed workers, earned income tax revenues at the municipal level, non-profit fundraising in Pennsylvania, rural acute care hospitals, and the needs of our state’s older residents. The eligibility requirements and guidelines for submitting a Letter of Intent are on the Center’s website, listed below.

The Pennsylvania Rural-Urban Leadership (RULE), a longtime partner of the Center, is also starting a new season by recruiting class members for its upcoming leadership class. RULE is accepting applications for its two-year leadership development initiative. The program, which partners with Penn State University, focuses on developing proficiencies in communication skills, group process, personal leadership and specific community issues. The first year emphasizes local, regional and state public policy issues, and the second year focuses on national and international issues. If you think you, or someone you know, would be a good candidate for this leadership program, call (814) 863-4679 or visit www.rule.psu.edu.

With the new legislative session underway, the Center’s Board of Directors held its reorganization meeting. I want to thank the board members for their support in re-electing me as chairman. The Center is well-served by my fellow officers and board members, all of whom were reappointed by their respective organizations. We all remain committed to the fine work of the Center and ensuring that our products and services continue to inform public policy debate in Harrisburg and provide practical tools and resources to local officials and communities.

Senator Gene Yaw

Center Board Elects Officers for 2013-2014

At its March meeting, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania’s Board of Directors elected officers for the 2013-2014 legislative session. The board reelected Senator Gene Yaw chairman and Dr. Nancy Falvo secretary. The board elected Senator John Wozniak vice chairman and Representative Garth Everett treasurer.

|

Pictured: Sen. Gene Yaw, chairman; |

Rural Snapshot: Young Families

In 2011, there were an estimated 157,600 young families in rural Pennsylvania, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Public Use Microdata Sample (ACS-PUMS). That’s 14 percent of all families in rural Pennsylvania. Young families in urban Pennsylvania totaled 331,500, which was 16 percent of all urban families.

Here’s how the Center defined young families. First, it used the Census Bureau’s definition of “family” as follows: a family is comprised of two or more people who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption and who reside in the same housing unit.

It then defined a family as “young” when the reference person in the family was between the ages of 18 and 34 years old. The reference person, or householder, is the person who owns or rents the housing unit in which the family lives. If the house is owned or rented jointly by a married couple, the householder may be either the husband or the wife. The person designated as the householder is the “reference person” to whom the relationship of all other household members is recorded.

Nationwide, there were 13.8 million young families, or 18 percent of all U.S. families. The three states with the highest percentage of young families were Utah, Alaska and North Dakota, each with more than 23 percent of all families. The three states with the lowest percentages of young families were New Jersey, Vermont and Connecticut, each with less than 15 percent. Pennsylvania, with 15 percent of families between 18 and 35 years old, had the nation’s 44th highest percentage of young families.

Types of Young Families

There are two types of young families: married and non-married. Married families are comprised of a husband and wife and non-married families are made up of two or more related persons. Examples of this category include a single parent with children, an older relative living with a younger person, or siblings living together. In 2011, the Census Bureau did not classify same sex partners as a family.

In 2011, 63 percent of young rural families were married and 37 percent were not married. Among young urban families, 56 percent were married and 44 percent were not married.

Eighty-three percent of young rural families had children and 17 percent did not. Those with children had an average of 1.6 children. In comparison, fewer young urban families had children (76 percent) and those with children had, on average, fewer children (1.4).

Sixty percent of young rural families with children were married and 40 percent were not. Forty-nine percent of young urban families with children were married and 51 percent were not.

Minorities

In rural Pennsylvania, 8 percent of young families were minorities (non-white/Hispanic). In comparison, 5 percent of older rural families (35 years and older) were minorities. In the state’s urban areas, 37 percent of young families and 21 percent of older families were minorities.

Housing

Fifty-six percent of young rural families were homeowners. In 2011, the estimated median property value for their homes was $125,000. Approximately 16 percent of these families owned their home and 84 percent had a mortgage. In 2011, the median monthly mortgage payment for these families was $760.

Forty-four percent of young rural families rented their homes. On average, these families lived in a home with 2.7 bedrooms and paid a median monthly gross rent of $743.

Among young urban families, the majority rented their homes (53 percent). These families lived in a home that had an average of 2.4 bedrooms and paid a median monthly gross rent of $900. Forty-seven percent of young urban families were homeowners, most of whom (91 percent) had a mortgage payment. The median monthly payment for these families was $1,100. In 2011, the estimated median value of their homes was $170,000.

Seventy percent of young rural families and 73 percent of young urban families lived in the same home for less than five years.

In 2011, the typical young rural family spent about 23 percent of their income for housing. Those who rented spent more (29 percent) than homeowners (20 percent). Young urban families spent about 26 percent of their income on housing and renters paid more than homeowners (32 percent and 23 percent, respectively).

Vehicles

On average, rural young families had fewer vehicles than older rural families (1.8 and 2.2 vehicles, respectively). There was a similar pattern among young and older urban families. In addition, the commute time for young rural family householders was slightly longer (26.5 minutes) than it was for older rural family householders (26.1 minutes). There was a similar pattern among young and older urban family householders as well.

Employment

Almost all young rural families (92 percent) had at least one family member who was employed. Among these families, 46 percent had one employed family member; 52 percent had two employed members; and 2 percent had three or more employed members. There was a similar pattern among young urban families.

Forty-seven percent of young rural families with children had one employed member; 43 percent had two or more employed members; and 10 percent had no employed members. In comparison, 17 percent of young rural families without children had one employed member; 80 percent had two or more employed members; and 3 percent had no employed members.

Among young urban families with children, 51 percent had one employed member; 38 percent had two or more employed members; and 11 percent had no employed members. The employment pattern among young urban families without children was similar to young rural families without children.

In 2011, young rural and urban family householders had nearly similar unemployment rates: 10 percent for rural and 9 percent for urban. These rates, however, were above the rates for older family householders. Among rural older family householders, the unemployment rate was 5 percent and among urban family householders it was 7 percent.

Educational Attainment

Young rural family householders had higher educational attainment levels than older rural family householders. In 2011, 24 percent of young rural family householders and 22 percent of older rural family householders had a bachelor’s degree or higher. For urban families, the educational attainment levels between younger and older householders were not as pronounced: 33 percent of young urban householders and 33 percent of older urban householders had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Income and Poverty

For young rural families, their 2011 median family income was $42,766. The median income for older rural families was $60,280. For young urban families, the median income was $47,857, and the median income for older urban families was $71,073.

Not surprisingly, families with more employed members had higher incomes than families with fewer employed members. Young rural families with one employed member had a median income of $26,678, while those with two or more employed members had incomes of $67,204. There was a similar pattern for young urban families.

Young families were more likely to live in poverty than older families. The poverty rate for young rural families was 24 percent and the rate for older rural families was 6 percent. For young rural families with children, the poverty rate was 28 percent. The rate for those without children was 7 percent.

Twenty-two percent of young urban families and 8 percent of older urban families were in poverty. For young urban families with children, the poverty rate was 28 percent and for those without children, the rate was 4 percent.

Change in Young Families

Data from the 1990 and 2010 decennial censuses indicate a national decline in the number of young families. Across the U.S., young families declined 16 percent from 1990 to 2010. In Pennsylvania, there was a 29 percent decline in young families from 1990 to 2010, and among rural counties, there was a 35 percent decline.

In 1990, young families made up 26 percent of all families in the U.S. In 2000, the percentage dropped to 21 percent, and in 2010, it dropped to 18 percent. In Pennsylvania, young families made up 23 percent of all families in 1990. In 2000, the percentage dropped to 18 percent and in 2010, it dropped to 16 percent.

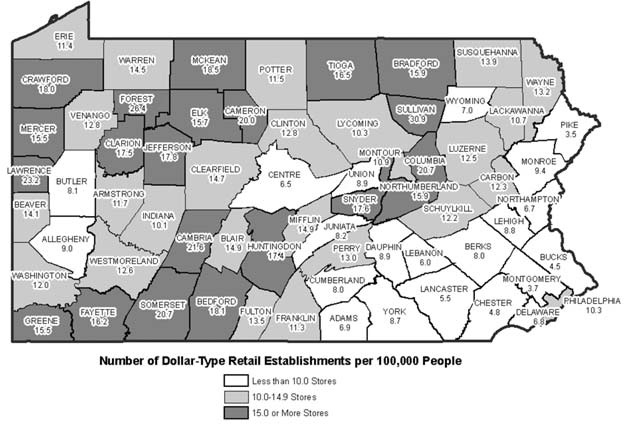

A Dollar a Dozen? Dollar-Type Retail Stores in Pennsylvania

Dollar-type retail stores seem to be everywhere these days. But how many of these stores are in Pennsylvania? According to 2013 data from the Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry, there are 1,226 dollar-type retail stores in Pennsylvania. Of that total number, 469 are located in rural areas. That’s about 13.5 dollar-type retail stores for every 100,000 residents. In urban areas, there are 757 dollar-type retail stores, which translate into about 8.2 stores for every 100,000 residents. Urban areas have the majority of dollar-type retail stores (62 percent), but rural areas have more stores per capita.

Compared to other states, Pennsylvania is on the higher end of the spectrum when it comes to the number of dollar-type retail stores. A 2011 study by research agency Colliers ranked Pennsylvania 6th nationwide, according to the number of dollar-type retail stores it had statewide. Texas came in first, with 2,243 dollar-type retail stores, followed by Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, and Georgia.

Number of Dollar-Type Retail Stores by County, 2013

Data source: Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry.

Did You Know . . .

- From the third quarter of 2010 to the third quarter of 2012, employment in rural Pennsylvania increased 1.5 percent. Over the same period, the number of employers increased 1 percent. In urban Pennsylvania, there was a 1.5 percent increase in employment and a 2.7 percent increase in the number of employers. (Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry)

- From 2010 to 2012, the number of vehicles registered in rural Pennsylvania increased by 35,343 or 1.0 percent. In urban Pennsylvania, the number of vehicles increased by 38,848, or 0.5 percent. (Pennsylvania Department of Transportation)

- In 2010, there were 493 hotels and motels in rural Pennsylvania. (U.S. Census Bureau)

Just the Facts: Rural Tourism

After a few sluggish years, tourism expenditures in rural Pennsylvania are beginning to climb.

According to the most recent data from the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, visitor spending increased 5 percent from 2010 to 2011, from $11.2 billion to $11.7 billion.

Tourism employment also increased about 1 percent from 91,585 jobs in 2010 to 92,948 jobs in 2011.

Tourism expenditures in urban Pennsylvania climbed as well, with a 6 percent increase in visitor spending from $24.0 billion in 2010 to $25.4 billion in 2011. Tourism employment in urban areas increased about 2 percent from 194,891 jobs in 2010 to 198,529 jobs in 2011.

Statewide, from 2010 to 2011, tourism expenditures increased in the spending categories of transportation, food and beverage, recreation, shopping, and lodging.

In rural and urban Pennsylvania, the highest spending occurred in transportation, where visitors spent $3.6 billion in rural areas and $9.3 billion in urban areas. In both rural and urban Pennsylvania, visitors spent the least on lodging: $1.4 billion in rural areas and $3.4 billion in urban areas.

It appears that the rising price of gasoline was a contributing factor to increased spending among leisure and business visitors statewide. Spending among Pennsylvania leisure and business travelers rose 9 percent from 2008 to 2011 from $36.2 billion to $37.2 billion.

In addition to increased gasoline prices, hotel rates rose and travelers purchased more goods and services during travel times.

Visitor Spending in Rural Pennsylvania, 2010 to 2011

Data source: Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development.