Newsletters

- Home

- Publications

- Newsletter Archive

- Newsletter

March/April 2008

Inside This Issue:

- Research Examines Schools’ Progress in Meeting No Child Left Behind Mandates

- Chairman’s Message

- EITC Helps Low- to Moderate-Income Individuals, Families Keep More of What They Earn

- Small Rural District First to Offer Chinese Language Lessons to El Ed Students

- Study Says Additional Funds Needed to Meet State Performance Targets

- How Pennsylvanians Are Connecting to the Internet

- Just the Facts: Number of Pennsylvania Charter Schools is Growing

Research Examines Schools’ Progress in Meeting No Child Left Behind Mandates

Are the goals of the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) law being met in Pennsylvania’s rural and urban schools? For the most part, yes, according to research conducted by Dr. Patricia Smeaton and Dr. Faith Waters of East Stroudsburg University and sponsored by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania. However, administrators in both rural and urban schools are very concerned about being able to meet the mandates as the requirements increase in the next few years.

Research background

NCLB, or H.R. 1 of 2001, was designed to strengthen the achievement of kindergarten through 12th grade students across the United States. NCLB brought two new measures to education: all students must achieve at a proficient level and all stakeholders, educators, students and parents will be held accountable to meet that goal. To help schools improve, their progress must be ascertained and then initiatives implemented that will support improvement efforts.

To provide a more comprehensive, data-driven picture of the progress Pennsylvania’s rural and urban schools are making in meeting the NCLB mandates, the researchers conducted the study in 2005-2006 using four data sources: reports from the Pennsylvania Department of Education; two online surveys, one for principals and one for superintendents throughout Pennsylvania; focus group discussions and interviews with survey respondents; and a summary of interviews of principals of high performing rural schools. The data provide a thorough picture of how Pennsylvania’s schools are succeeding in meeting the NCLB mandates.

The researchers’ analyses of the data helped to provide a picture of the continuing needs of schools and develop policy considerations for additional program and policy support for all schools, with particular emphasis on the needs of rural schools.

Meeting the mandates

The research found that while most schools are currently meeting the NCLB mandates, both rural and urban administrators are very concerned about being able to meet the mandates as the requirements increase over the next few years. The administrators believe 100 percent proficiency by 2014 is unrealistic.

The research also found that rural and urban administrators were in agreement as they identified special education, funding, and achieving proficiency as the three major concerns they face in meeting the NCLB mandates.

However, there are some differences between rural andurban school districts in terms of the obstacles they face and the initiatives they are implementing to meet the challenges. More rural schools noted challenges associated with curriculum alignment while more urban schools reported challenges of student diversity and transience. While both rural and urban administrators cited delay in receiving Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) results as a problem, it was significantly more so for rural schools.

The research revealed a willingness on behalf of school administrators to meet the NCLB mandates and the belief by school administrators that NCLB was having the intended effect of increasing student achievement. The administrators also identified the Pennsylvania Department of Education’s initiative of identifying assessment anchors as extremely beneficial and an example of meaningful support. The study also found that unless federal modification occurs, very few schools would be able to meet Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) requirements as the proficiency scale increases to an absolute 100 percent.

Policy considerations

From the study, the researchers identified several policy considerations for state and federal policymakers and educational leaders.

For state and federal decision makers, the considerations include the need to: address and modify subgroup accountability, especially in regard to special education; increase funding and make the mechanism for funding more flexible and responsive to local needs; and consider whether 100 percent of students scoring at the proficient level on the same high-stakes test is a realistic goal.

The considerations for rural schools include: offering additional professional development opportunities; forging stronger parent and community relations; and maintaining small schools or restructuring to create communities within schools.

Report available

For a copy of the research results, A Statewide Investigation into Meeting the Mandates of No Child Left Behind, call the Center for Rural Pennsylvania at (717) 787-9555, email info@ruralpa.org or visit www.ruralpa.org.

Chairman’s Message

If you quickly scanned this issue’s table of contents, you no doubt noticed a definite theme of education running through the pages. From the research on No Child Left Behind on Page 1 to a quick “Just the Facts” look at the growth of charter schools on Page 7, this newsletter offers a glimpse at a variety of education-related topics that are getting a lot of attention these days.

Our cover story presents the results of research on Pennsylvania school districts and their efforts to meet the mandates of No Child Left Behind, or NCLB, the sweeping federal law that mandated achievement and accountability standards for students and schools. Much has been reported on NCLB nationwide, and the way in which schools are working, or in some cases struggling, to meet the mandates of the law.

According to the research, sponsored by the Center, rural and urban Pennsylvania schools are meeting the mandates of the law, for the most part, but may find those goals difficult to meet in the coming years as they strive to reach 100 percent proficiency by 2014.

The research also revealed that school administrators are working hard to meet the requirements of the law and believe that student achievement is increasing.

The researchers point to several policy considerations for both state and federal policymakers and educational leaders that will help schools continue to make progress and overcome several obstacles that are hindering their success.

This issue of Rural Perspectives brings to your attention a fine example of how a small, rural school, with innovation and community support, can literally bring the world to its classrooms and students.

On Page 4, we feature Glendale School District, which has a K-12 student population of around 880, and encompasses an area of about 100-square-miles in both Cambria and Clearfield counties. While its student population puts the district in the bottom 10th percentile of all school districts for enrollment, Glendale continues to think big when it comes to implementing programs to improve learning. Starting in the fall of 2007, Glendale began offering instruction in Mandarin Chinese to all of its kindergarten and elementary school students, and to some students in the junior and senior high schools.

According to Dr. Dennis Bruno, Glendale’s superintendent, research on how early language learning positively affects student achievement played an important role in motivating the district to pursue this initiative. The support of the school board, parents, community and area businesses was critical in getting the initiative going. Pennsylvania’s Accountability Block Grant and assistance from a foreign ministry enabled Glendale to hire a teacher from Taipei, Taiwan.

While it is too early to determine the impact of this language program on student proficiency and achievement, Dr. Bruno believes this investment will provide many returns. His belief is reinforced each time he sees the excitement of the elementary students as they practice new words with their new teacher.

While much education policy and funding focuses on our K-12 students in the classroom, we all need to remember that education and learning is a lifelong process. So, take a few moments to read through this issue and learn more about rural Pennsylvania. I know I did.

Senator John Gordner

EITC Helps Low- to Moderate-Income Individuals, Families Keep More of What They Earn

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) program assists low- to moderate-income working individuals and families by providing a refundable federal income tax credit. The United States Congress approved the program in 1975 in part to offset the burden of social security taxes and to provide an incentive to work. Eligible taxpayers who qualify for the credit receive a tax refund when the EITC exceeds the amount of taxes owed. To qualify, taxpayers must have worked at some point during the year, and have an income with prescribed limits that are adjusted for the number of family members and children.

The EITC has no effect on certain welfare benefits, and, in most cases, is not used to determine eligibility for Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, food stamps, low-income housing or most Temporary Assistance for Needy Families payments.

Get money back

In tax year 2005, data from the federal Internal Revenue Service (IRS) showed that in the United States, 22.7 million Americans, or 17 percent of all tax filers, received EITC. These credits totaled $42.6 billion, or an average of $1,874 per EITC taxpayer. In Pennsylvania, 779,963 taxpayers, or 14 percent of all tax filers, received EITC. These credits totaled $1.3 billion, or an average of $1,722 per EITC taxpayer. Among the 50 states, Pennsylvania ranked eighth in the number of taxpayers who used EITC, and ninth in total credits.

In Pennsylvania, in 2005, 28 percent of EITC filers were from rural areas and 72 percent were from urban areas. The total tax credit returned to rural EITC filers was $361 million, or an average of $1,661 per EITC filer. In urban areas, the total tax credit returned to EITC filers was $933 million, or an average $1,702 per EITC filer. Since the amount of credit is determined by family size and income, the EITC can be an effective tool to help low- to moderate-income working families and individuals keep more of what they earn.

Some missing out

To help states understand how many individuals and families may be missing out on EITC, West Central Initiatives, a Minnesota-based nonprofit organization, developed a statistical model to identify how many eligible households are not participating in EITC. Applying this model to rural Pennsylvania shows that, in 2005, 27 percent, or 82,200, of all eligible households were not participating. If these households were to participate, it would result in an additional $136.4 million in income to rural Pennsylvania’s low- and moderate-income households.

In Pennsylvania urban areas, the model indicated that, in 2005, 20 percent, or nearly 139,000, of all eligible households were not participating in EITC. If these households participated, $236.4 million would be returned to these low- to moderate-income urban households.

Help with filing

To ensure that all qualified persons participate in the program, nonprofit organizations and federal and state agencies are providing outreach and educational services about EITC.

The IRS’s Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) Program and Tax Counseling for the Elderly (TCE) Program are two programs that offer free tax help to qualified taxpayers.

For the VITA Program, certified volunteers sponsored by various organizations receive training to help prepare basic tax returns in communities across the country. VITA sites are generally located at community and neighborhood centers, libraries, schools, shopping malls, and other convenient locations. Most locations also offer free electronic filing.

The TCE Program provides free tax help to people age 60 and older. Trained volunteers from non-profit organizations provide the free tax counseling and basic income tax return preparation. These volunteers are often retired individuals associated with non-profit organizations that receive grants from the IRS.

To locate a VITA or TCE site or for more information about either program, call toll free (800) 829-1040.

For more information on EITC, visit the IRS website at www.irs.gov.Small Rural District First to Offer Chinese Language Lessons to El Ed Students

The young woman stands in front of the children holding an oversized flash card painted green. She walks around the second grade classroom with the flash card, saying a word that’s foreign to the children’s ears, making sure everyone in the room sees the card and is repeating the word correctly. These seven-year-olds are learning to speak Mandarin Chinese. What’s surprising is that these children are part of a small, rural Pennsylvania school district.

Glendale School District, which straddles Cambria and Clearfield counties, is providing lessons in Mandarin Chinese to every kindergarten through sixth grade class and to one class in each of the junior and senior high schools.

“Research shows that learning a language at an early age helps children in all capacities,” said Dr. Dennis Bruno, Glendale superintendent. “Our district is looking to improve our PSSA scores just like every other district in the state, and our district believes that early exposure to other languages will help our students be more successful.”

Growing an idea

The idea to offer Mandarin Chinese to Glendale School District students came to Bruno during the 2006-2007 school year when he noticed how quickly a young foreign exchange student was learning to speak English, and how her self-confidence was growing along with her language skills. The overwhelming research on how studying a second language can boost student achievement also convinced him and the district that offering a foreign language to all elementary students would be worth pursuing. The district chose Mandarin Chinese because so few public schools were offering the language to their students.

In the summer of 2007, Bruno worked with a representative from the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in New York City to bring a native Mandarin Chinese speaker to the district.

Through its work with PDE, the district received a Pennsylvania Accountability Block Grant, which was established by PDE for school districts to attain and improve academic performance targets. The grant, awarded under the World Language in Elementary Grades program, helped the district pay for the language teacher’s salary for one year.

With the help of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, Bruno was able to travel to Taipei, Taiwan to interview potential teachers. During his visit, he hired teacher June Chen, who then came to Pennsylvania just as the 2007 school year was ready to begin.

“The school board, community, and businesses have been very supportive of our efforts to offer this new language instruction to our elementary and secondary school students,” Bruno said, “And the community has helped make the transition for June much easier.” For example, when Chen first arrived in the United States, Bruno and his family helped her to apply for a driver’s license, and introduced her to community residents. A local nonprofit group helped Chen furnish an apartment in the community of Bellewood.

Establishing a cyber school

As Glendale School District carries out its goal of providing Mandarin Chinese lessons to its students, it is making progress on another goal to offer other Pennsylvania elementary students the opportunity to learn the language via the Internet.

“We would like to start a cyber school in the fall of 2008 and offer Mandarin Chinese classes to other districts in Pennsylvania,” Bruno said, adding that several districts in the central Pennsylvania area have expressed interest. Eventually, Bruno would like to offer the classes to districts nationwide.

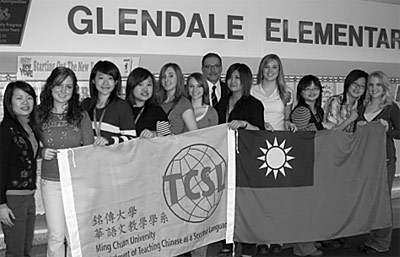

To help prepare the cyber school’s course work, the district hosted five student teachers from Taipei’s Ming Chuan University in January and February 2008. The student teachers assisted Chen with the elementary and secondary language lessons and helped develop an elementary curriculum for the online classes. In return, the student teachers received a crash course in American culture, as they lived with the families of the five senior high students who are studying Chinese, and were able to practice their English.

According to Bruno, the hosting experience has been positive for the Glendale students and student teachers, as it has offered all the opportunity to improve their language skills and broaden their cultural experiences.

And while it’s too early to evaluate the benefits of the overall language initiative, several teachers have noted that the students, especially those in the first and second grades, have been enthusiastic about the classes. For some, this enthusiasm has spilled over into their traditional course work.

“I think it’s great that a small, rural school can offer this kind of initiative to its students and potentially offer it to other students in districts across the state and the nation,” Bruno said. “I believe this initiative will create new opportunities for our school district and, most importantly, new opportunities for our students.”

Nini Yu, a student teacher from Ming Chuan University of Taipei, Taiwan, teaches Mandarin Chinese

to a Glendale School District second grade class.

June Chen, left, together with five student teachers from Ming Chuan University of Taipei, Taiwan, are developing an elementary Mandarin Chinese language curriculum for the Glendale School District’s proposed cyber school. Dr. Dennis Bruno, center, and the five senior high students whose families are hosting the student teachers are also pictured.

Study Says Additional Funds Needed to Meet State Performance Targets

In November 2007, the Pennsylvania State Board of Education released the results of a study to identify the resources needed for all students in Pennsylvania to achieve state proficiency goals in reading and math by 2014, and to master state standards in 12 academic areas. Act 114 of 2006 mandated the Board of Education to complete the study, Costing Out the Resources Needed to Meet Pennsylvania’s Public Education Goals.

According to the study results, Pennsylvania school districts will need substantial additional funding to meet the state’s specific performance targets. For example, the study results noted that, in 2005-2006, the commonwealth would have needed to spend a total of $21.6 billion, or $11,926 per student, to meet proficiency goals. This cost did not include transportation, food services, community services, adult education, or capital expenditures.

Currently, districts in rural Pennsylvania spend an average of $9,232 per pupil in educational costs. To meet state goals by 2014, rural schools would need to spend approximately $11,409 per pupil. Together, Pennsylvania’s rural districts would need to spend $7.3 billion to meet the state’s performance targets.

Of the state’s 501 school districts, 471 are not meeting the per student costs identified in the study. Among Pennsylvania’s rural school districts, only three were spending the amount identified in the study results: Forest Area School District in Forest County, State College Area School District in Centre County, and Sullivan County School District in Sullivan County.

Instead of funding education with local revenue, the study recommends that funding should be collected at the state level. The state should then allocate funding through a formula that is sensitive to the individual needs and wealth of school districts. The study noted that, in Pennsylvania, districts with the highest need tend to generate the least amount of local revenue, while districts with the lowest need tend to generate the most local revenue.

The study suggests that, once school districts had the appropriate funds per pupil, they would be expected to use the additional collected funds to support students with special needs, reduce class sizes, and hire additional counselors, nurses, instructional facilitators, tutors and security personnel. School districts would also be encouraged to implement full-day kindergarten, expand the school day and summer school for low performing students, target professional development, and expand the use of technology and associated training for teachers.

For a copy of the study, visit the Pennsylvania Department of Education’s website at www.pde.state.pa.us.

How Pennsylvanians Are Connecting to the Internet

To examine how Internet connectivity in rural and urban Pennsylvania has changed over the past few years, the Center for Rural Pennsylvania compared and analyzed data from three sources and found that there are three distinct “divides” among rural Pennsylvania households and among rural and urban Pennsylvania households.

The Center used the following data sets to measure Internet access among rural and urban households: the Center’s 2003 Attitudinal Survey of Rural Residents, which collected some information on rural residents’ Internet access, connectivity, and use; the 2007 Rural Pennsylvania Current Population Survey (RuralPA-CPS), which is closely modeled after the March Supplement of the federal Current Population Survey (CPS); and a December 2006 survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, which was used to compare rural Pennsylvania with the nation.

The results

Data from the RuralPA-CPS found that 66 percent of rural households had Internet access and 34 percent did not. From 2003 to 2007, the percent of rural households with Internet access increased 3 percentage points.

Rural households with Internet access were typically younger, more affluent, and more educated than households without Internet access. For example, the average age of persons living in households with Internet access was 38 years old while the average age of persons in households without Internet access was 53 years old. Also, the median income in households with Internet access was $60,000, while the median income for households without access was $24,000. Among adults (18 years old and older) in households with Internet access, 28 percent had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 7 percent of adults in households without access had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

There was a significant gap between rural and urban households with Internet access. In 2007, 72 percent of urban households had Internet access and 28 percent did not. In rural areas, 63 percent of households had Internet access and 37 percent did not.

In 2007, 62 percent of rural households with Internet access connected to the Internet using a broadband connection while 38 percent used a dial-up modem.

The method used to access the Internet was nearly evenly divided into thirds: 32 percent used a cable modem; 30 percent used a DSL connection; and 38 percent used a dial-up modem. From 2003 to 2007, the largest increase was in DSL connectivity (27 percentage point increase) followed by cable modem (14 percentage point increase). The use of dial-up modems declined 40 percentage points.

Among urban households with Internet access, in 2007, 74 percent connected to the Internet using broadband and 26 percent used dial-up.

Nationally, 74 percent of adults with a home Internet connection used broadband and 26 percent used dial-up. Among the adults in rural areas, 66 percent used broadband at home and 34 percent used dial-up.

Fact sheet available

For the complete fact sheet, How Are You Connected?, call the Center for Rural Pennsylvania at (717) 787-9555, email info@ruralpa.org or visit www.ruralpa.org/fact_sheets.html.

Just the Facts: Number of Pennsylvania Charter Schools is Growing

The number of charter schools is growing in Pennsylvania, according to data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Statewide, the number of charter schools increased from 65 to 119 from 2000 to 2006. Charter schools, which were established by Act 22 of 1997, are self-managed public schools that are approved by local school districts. They are created and controlled by parents, teachers, community leaders, and colleges or universities, and operate free from many educational mandates, except for those concerning nondiscrimination, health and safety, and accountability.

In rural areas, the number of charter schools increased twofold, from six schools in 2000 to 12 schools in 2006. In urban areas, the number of charter schools increased from 59 schools in 2000 to 107 schools in 2006.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2005, there were 3,623 charter schools nationwide. The states with the largest numbers of charter schools were California, Arizona and Florida. Pennsylvania ranked 10th among states in the number of charter schools.

Statewide, from 2000 to 2006, there were considerable increases in charter school enrollment. In 2000, there were 636 students enrolled in rural charter schools; in 2006, this number rose to 1,927 students. During the same time period, urban counties experienced enrollment increases from 18,345 students to 58,049 students.